«Are these rocks or are they clouds?»

The lesser known, more authentic Dolomites. A loop that starts and ends in Belluno, through uncontaminated places, in the name of pure wonder.

Period

Apr - Oct

Elevation difference

4490 m

Total Length

236 km

Duration

3/4 Days

P

I write all this from a position that is anything but neutral, because I was born in Belluno, I live there, will die and even resurrect in this province, as the poet said. I will also admit right away that one of the most difficult things of talking about this journey will be avoiding to fill it up with quotations from Dino Buzzati, surely the greatest of Belluno’s writers, among the greatest of the 20th century in general.

It will be difficult, and in fact I am already starting badly, as I steal his words to say something that numbers, with all their precision, cannot describe: “If I say that my homeland is one of the most beautiful places not just in Italy but in the entire terraqueous globe, everyone falls from the clouds and stares at me with amused curiosity. My homeland, in fact, is called Belluno, and although it has its own province, I’ve come to notice over the decades that almost no one, except the people of Belluno, knows where it is.”

We could stop here. One of the greatest Italian writers of the last century has just told you that his home is one of the most beautiful places in the world, plus the area is notoriously teeming with climbs, descents and mountains. And I could conclude this exhortation as follows: take your bike, load it in the car or on the train or bus and just ride around Belluno as long as you like. Either way, wherever you go, it will be beautiful. The end. But I need to fill in a few hundred more lines, plus we are here to tell a story about a trip, give a little advice, convey some of the emotion…so we’d better get started.

From Belluno we set off northward, going up the Piave River. After Ponte Nelle Alpi we crossed this river, which is sacred to our homeland, and took a brand new and indeed beautiful bike path, often riding just above the waters, in and out of tunnels so small it almost seems they finished digging them with pickaxes only an hour earlier, just for us.

This will also be a story of roads, water, rock and wood.

Just beyond Longarone-a long-forgotten story of tragic water and rock- the road traffic slips into a tunnel, this time a wide one, cemented and well-lit; but we instead turned right onto the old road.

The main road is well known, it is the one that leads straight into the belly of the mountains towards the holiday spots of Cadore, and from there to Cortina or Auronzo. Our route instead is virtually unknown. It’s hidden from view, caressing the body of the mountains and the bends of the river, gently touching the various towns along the course of the Piave: Termine di Cadore, Ospitale di Cadore, Rivalgo, Rucorvo, all the way to Perarolo di Cadore, which deserves a stop in the journey as it does in the story.

We stop for coffee at a bar called Covo dei Zatèr, just in front of the Museo del Cidolo. These are names coming from a time, admittedly not so remote, when Perarolo was an essential centre for the collection and sorting of all the wood that arrived from Cadore. This wood has always been the real wealth of the area.

It’s here, at the confluence of the Piave and the Boite rivers, that an artificial dam – called cidolo – was created. And from here large rafts – built and helmed by the zatèr from which the bar takes its name- departed for the Republic of Venice.

In the Serenissima Republic of Venice the foundations of palaces, narrow streets, bridges, and squares still lay on millions of logs coming largely from the forests of the Belluno area, which in its golden years shipped every year something like 350,000 trunks to the lagoon. Having now claimed fatherhood for Venice, as well as for the Dolomites, let us move on.

This centuries-old economic pattern cracked in the early twentieth century with the arrival of the railroad and, little by little, Perarolo lost its strategic role as a river port. In the 1980s, the construction of the Cadore Bridge and the tunnels connected to it permanently cut off the village and the Cavalera, until then the only real link between Longarone and Cadore, off the main tourist routes.

The result of this? Now there are very few cars, and the old road has become a playground for bike-travellers and touring cyclists. The managers of the Covo dei Zatèr tell us that every day from mid-April to the end of September no less than a hundred people on bicycles pass this way, many of them along the Munich-Venice route.

Water, wood and roads. We are still missing the rocks. We find them a little later in the colossal pyramid of the Antelao and the Marmarole group, the mountains overlooking Pieve di Cadore. Here in the late 15th century Titian Vecellio was born, better known simply as Titian.

At the age of nine he followed the zatèr to the lagoon, where he became one of the masterminds of innovation during the Renaissance, revolutionizing painting throughout the west by giving centre stage to colour, in an age still dominated by drawing.

He was the first – or if not quite the first, certainly one of the best- to paint the effects of light, shadows, depth and volume, in short, everything that could be painted using almost exclusively the infinite variations of colour.

Who knows if such a totalizing use of colour came to him from the memory of his mornings as a child, when he would see the sunrise mirrored on the walls of the Antelao and Marmarole mountains, turning them yellow, orange, pink, indigo and purple. A bit like how we see the sunset now reflected in the Centro Cadore lake at the end of our first stage.

The valley continues north and we follow it.

After Cima Gogna the Piave River turns toward its source below Peralba, we instead pull straight toward Auronzo, and shortly after take a beautiful dirt track for bikes through the woods.

However, this is actually not just any old wood, but the Somadida Natural Reserve, the largest forest in Cadore. It was already a protected area at the time of the – you guessed it- Republic of Venice, after the Magnificent Community of Cadore donated it to Venice in 1463 so that it could make ship masts from its trees for the war against the Turks.

At Somadida it feels as if we are still cycling in that old world, in a time when the Dolomites were just mountains without name or fame. So much so that it wouldn’t seem too strange to bump into two elegant gentlemen dressed in tweed, Josiah Gilbert and George C. Churchill, the two men who played a crucial role in the ‘discovery’ of the Dolomites.

Gilbert and Churchill were two Englishmen, one a painter and the other a naturalist, who in the second half of the 19th century deviated from the typical route of the Grand Tour set by European affluent classes, and ventured up here, fascinated by the figure of Titian and the landscapes that served as the backdrop for many of his paintings.

Between 1861 and 1863, together with their wives, they toured the length and breadth of the valleys, the first foreign travellers to do so, and once back home they co-wrote a book: The Dolomite Mountains. The name Dolomites already existed, in honour of the French geologist Déodat de Dolomieu who discovered the unique peculiarities of these limestone rocks, but it was that book, embellished with Gilbert's watercolours, that marked the beginning of the fame of these mountains around the world.

After Somadida we leave the dirt track and get back onto asphalt, taking a left to the Tre Croci pass. But it’s worth mentioning a road we will not take today. A road that, a little further on, climbs from Misurina up to 2,333 meters at the Auronzo mountain refuge, just below the Tre Cime [Three Peaks] of Lavaredo. This (toll) road has been in the news several times in recent years for the mile-long queues that increasingly pile up during the summer, with the inevitable corollary of controversy from tourists and residents.

It is a sensitive issue, and in difficult matters it is always best to rely on something solid. As luck would have it, Dino Buzzati spoke about this road on the eve of its construction, in the Year of Our Lord 1952, in an article in the Corriere della Sera entitled Rescuing the Tre Cime di Lavaredo from car traffic.

I report only a few brief excerpts.

“So, tourist will come in crowds, new restaurants, hotels, kiosks, garages, etc. will open. Many people who are unemployed now will have a job. This is true. But one can quote the story of that fellow, whose cow's milk not being enough for the family, had the good idea of butchering it. Yes, wife and children gorged themselves on meat. But then what? Surely long processions of Italian and foreign cars will come, francs, dollars and pounds will come. But then what? Are we sure the numbers will add up? (...) The mountains will still be there, surely, but defaced, involuted, stupefied, reduced to meaningless piles of stone. The road, they say, will bring dollars and pounds. At this rate why not sell museum masterpieces to America? It really makes no difference.”

Buzzati wrote all this seventy-two years ago. Yet, it is hard to think that the future, of these places and beyond, is not prophesised by these words.

Not least because to avoid queues, jitters, pollution, and in general all the misfortunes connected with the famous phenomenon of overtourism, the solution would be simple. The solution being what Destinations in general, and this little report in particular, suggests. Come here on your bicycle.

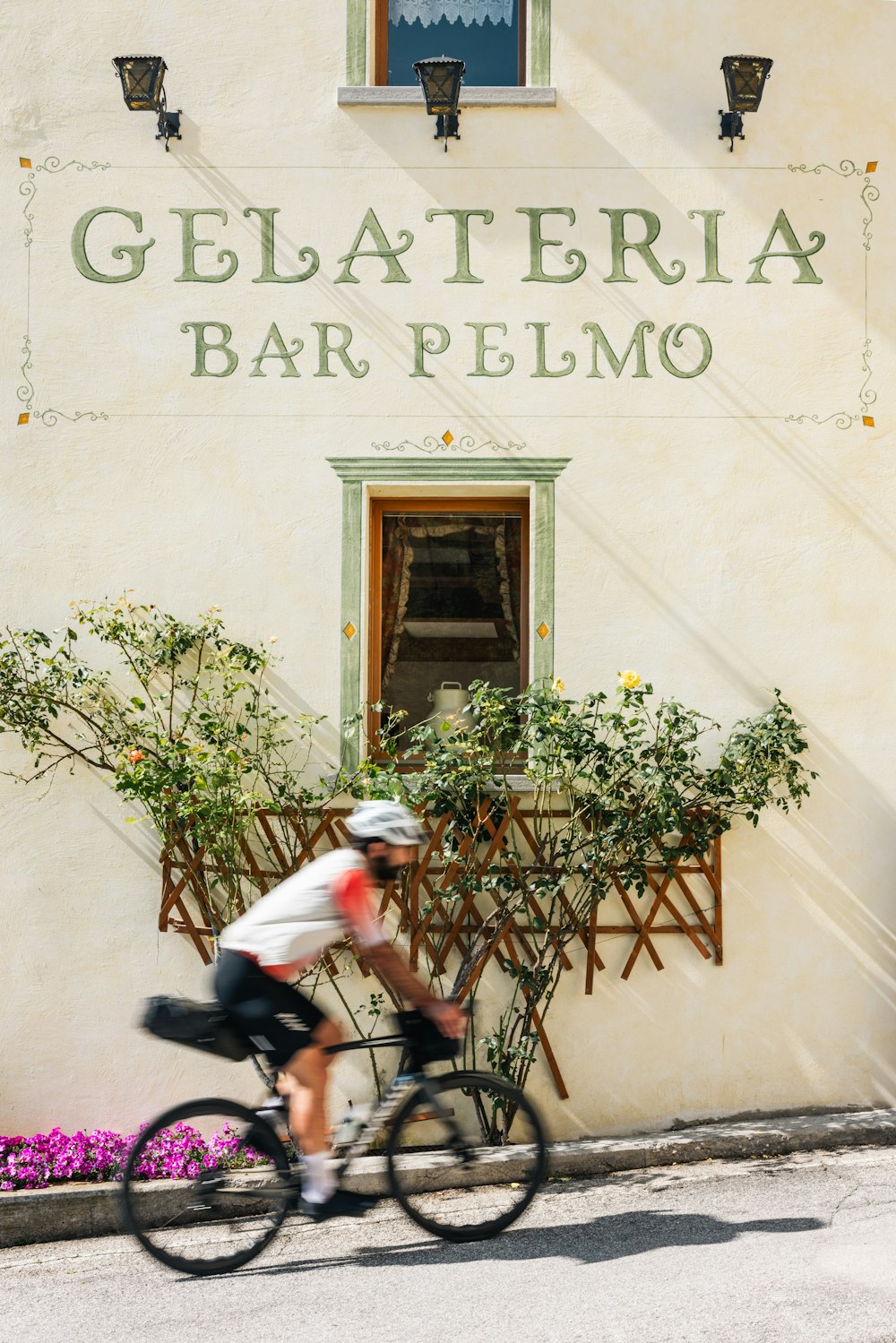

From the top of Passo Tre Croci the Ampezzo basin opens up, which however you think of it is still a treasure trove. But our bicycles take us away along the bike path of the old Calalzo-Cortina railway, in front of us the Antelao reappears and to the right of it the unmistakable silhouette of Pelmo, the Caregon del Signor.

At Venas we turn right and take a much lesser-known climb, the Cibiana Pass. Before descending we stop in Cibiana di Cadore to see its famous murals, a tribute by dozens of artists from all over the world to the history of the village.

From the Cibiana Pass we enter the Zoldo Valley. Geographically speaking Zoldo is the valley between the Pelmo and Civetta massifs, two of the most beautiful and recognizable mountains in the world. It is famous for its tabià, traditional stone and wood buildings, for its larch forests, and for its artisans who have taken the art of ice cream all around the world.

However, this is not enough, assuming it can be done, to render the atmosphere of this slice of the Dolomites.

Again, luck would have it that someone spoke of it first and best, as in the case of Sebastiano Vassalli, who set one of his most famous works, Marco and Mattio, right here. The book tells the story of Mattio Lovat, one of the first clinical cases of Italian psychiatry, actually just one of the many people of these mountains to be plagued by hunger in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Vassalli wrote, “Zoldo is not a village nor the valley named after its river, but it is-or, rather, was-a dimension of the spirit.” Zoldo, in short, is a state of mind.

Another example of the spirit of Zoldo is the Traiber sawmill that we pass at the end of the Cibiana descent. It is the only sawmill left in Zoldo and for over a hundred years it has survived dealing only with local larch, the wood used for centuries to build houses and tabià.

After a mandatory stop at the famous Dont ice cream parlour, we tackle the Duran Pass that leads to Agordo.

The descent is fast, the road narrow, very few cars pass here, no coaches whatsoever, motorcycles just a few and almost by mistake. All this certainly makes Duran one of the most enjoyable climbs in the whole Province.

In Agordo we stop for coffee. Around us a whole series of peaks, some clearly visible others less so, but all of which have made history in world mountaineering. Behind us are San Sebastiano and Moiazza, the southern buttress of the Civetta massif, where in the 1920s Emil Solleder and Gustav Lettenbauer opened the first route considered to be a VI grade; in front of us the profile of the Pale di San Martino, among which stands out the Agner with its endless north face, climbed by the Messner brothers and where one winter day that titan who was Riccardo Bee fell to his death; to the right the Pale di San Lucano, rising vertically from the valley floor and then flattening out at the top, like a prehistoric archipelago.

Through the Val del Mis and the mysterious, wild profile of its Monti del Sole mountains we reach the end of the journey, cycling through tunnels dug by hand in the gorge created over millennia by the flow of the stream. Perhaps this is the most beautiful road of all of them.

We turn up back into the Valbelluna, and after a visit to the surprising Historic Bicycle Museum in Cesiomaggiore we head back toward Belluno, our departure and destination. Along the new bike path from Sedico to Belluno, we pedal in the light of sunset and arrive in Piazza del Duomo just in time to enjoy the Schiara, the locals’ favourite mountain, coloured orange for our pleasure.

The time has come dismount our bike, but not before a final tribute to Dino Buzzati and his love for this land.

“The Dolomites are also here in Belluno, and not second-rate Dolomites. The Schiara, which is right above, has a wall of wonderful colours absolutely on par with the most famous peaks. And from its ridge sprouts, most graceful, the Gusela del Vescovà or Needle of the Bishop, that is, a beautiful spire, a monolith, forty meters high. Belluno and its valley have a special personality that brings an extraordinary enchantment but which few people actually notice. Why? Because in the 'Val Belluna' there is a wonderful and almost unbelievable fusion between the world of Venice (with its serenity, classic harmony of lines, ancient refinement, the mark of its unmistakable architecture) and the world of the north (with the mysterious mountains, the long winters, the fairy tales, the spirits of the caverns and forests, that untranslatable sense of remoteness, solitude and legend).”

The place still holds that charm. As we drink our ceremonial beer, we see the Gusela mirrored among the Venetian mullioned windows of Palazzo Rosso, Belluno's City Hall.

And that really is, perhaps, the secret magic of this place.

A province that holds almost half of all the Dolomites, and at times seems not to know it. And that is precisely why it is still so beautiful

Texts

Fabio Dal Pan

Photos

Alessandro MimIola

Cycled with us

Fabio Dal Pan

This tour can be found in the super-magazine Destinations - Italy unknown / 3, the special issue of alvento dedicated to bikepacking. 9 little-trodden destinations or reinterpretations of famous cycling destinations.